Part 2 of 3

(originally published 6/18/20)

Last week the first in a 3-part series of Kansas City’s WWII experience laid the background on why the Kansas City area was able to land so many important defense plant contracts, considering the long tradition of military production plants located predominantly on the coasts. For this week and next, we’re going to look at some of the most noteworthy of those facilities – noteworthy for their importance, their impact, or the peculiar role they played. This week’s group might be called “the Big 3,” for they seem to be the most often mentioned among the plants, and for good reason.

Despite the genuine interest in supporting the war effort shared by Americans, the cities that landed these new defense plants were primarily looking to their post-war futures. An injection of the level of capital that building these massive facilities and employing the tens of thousands of workers would bring meant money to sustain the local economies through the lean war years, and, if all went as hoped, the jobs and the investment would continue for years after. Of all the Kansas City area plants, it’s easy to make the case that the first three, this week, did the most to create a lasting impact on Kansas City, albeit in different ways. The North American Aviation bomber plant in Fairfax cemented that relatively new (in 1940) district as one of the leading industrial locations in the midwest. Pratt & Whitney’s plant near 95th & Troost morphed over time into the Bannister Federal Complex that housed everything from the production of non-nuclear bomb parts to the regional processing center for the IRS for more than 60 years after the WWII production stopped. Lake City Army Ammunition Plant’s impact is hardest to calculate, because it’s in operation today, and with the exception of a short stand-by period, has stayed in production since the end of WWII.

NORTH AMERICAN AVIATION BOMBER PLANT – Fairfax Industrial District, Kansas City, KS

Location: The North American Aviation B-25 bomber plant was located in the Fairfax Industrial District, Kansas City, KS. The District covers 2,000 acres of bottom land just north of the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas Rivers, of which 75 acres was the site of the B-25 plant. The District is northeast of downtown KCK, and it connects by bridges to Kansas City, Missouri to the east and to the Parkville/Riverside area to the north. The district was created in 1923 by the Union Pacific Railroad, and lays claim to being the first planned industrial district in the country. Between its creation and the time the North American bomber plant was installed on the site, Fairfax housed facilities for railroads, foundries, refineries, construction firms, manufacturing plants, a lumber mill and an airport. All of these added to Fairfax’s attractiveness as a military production site, but so was the fact that the military was already highly invested in Fairfax. A naval reserve base was installed at Fairfax in 1935, one of several elimination bases in the country charged with screening candidates for final training as pilots.

Significance to the War Effort: The B-25, a medium-sized bomber, was ubiquitous in World War II, serving in every theaters of operation, and in the air forces of virtually every member of the Allied Forces. The plane was known as the B-25 Mitchell, named for General Billy Mitchell, considered the father of the US Air Force. On April 18, 1942, Lt. Col. “Jimmy” Doolittle led his squadron of B-25s in the bombing raid on Tokyo.

Operation: While the government owned the building and property, the plant was operated by a specially-formed subsidiary of North American Aviation. Over the course of the war effort, the plant was reported to have produced 6,608 planes, about 40 percent of all B-25s produced for WWII. Approximately 26,000 workers were employed at the plant.

Life after World War II: For a time, the government used the plant as the depot for selling its remaining B-25s to public and private buyers. Private carriers leased parts of the base for aircraft maintenance. But by far, General Motors accounts for most of the long-term use of the plant. Immediately following the war, General Motors leased the assembly buildings to produce both automobiles and – for a while – post-war military aircraft. After fifteen years as a lease holder, GM purchased the property from the government. The original B-25 plant was demolished for GM’s expansion, and a replacement (Fairfax II) was built in 1986. GM continues assembly operations there to the present.

PRATT & WHITNEY ENGINE PLANT – 95TH Street at Troost, Kansas City, MO

Location: The Pratt & Whitney Engine Plant sat about 300 acres at the northeast corner of 95th and Troost in Kansas City, Missouri. The site had originally been developed in 1922 as a 1.25 mile wood oval track for auto racing, known as the Kansas City Speedway. The track lasted only two years, and the property effectively sat dormant for almost twenty years. As an industrial site, the location had advantage of being close to Dodson, the small emerging industrial center to the east, and was adjacent to the streetcar line that ran along the property’s northern border, the Missouri Pacific rail lines that also ran through Dodson, the Blue River and major road transportation routes.

Significance to the War Effort: The plant was responsible for manufacturing and testing the 3,400 horsepower, R-2800-C engines. In the 2 ½ years of its operation, Pratt & Whitney produced 7,934 engines for a variety of planes that saw action in Europe and the Pacific, including the Army’s “Thunderbolt” and the Navy’s “Corsair” and “Hellcat,” three of the most critical American aircraft flown in WWII.

While the engines the Pratt & Whitney plant built were important in terms of performance, the plant’s design made a significant contribution, too. The war’s dependence on basic materials made steel a scarce commodity for construction, so the army hired famed industrial architect Albert Kahn to design their production facilities with as little steel as possible. Kahn’s concept used wide-span concrete arches. The material – concrete – was relatively cheap and far more forgiving in construction than steel. The 40-foot arches made possible huge expanses of uninterrupted floor space, adding flexibility to the use of the space. And the building process was much quicker, making it possible to serve the war effort faster.

Operation: At the peak of its war-time operation, Pratt & Whitney employed around 22,000 workers. When completed, the plant covered about 3 million square feet, the equivalent of about 69 football fields. The engines, mounted on trolleys, moved around the plant on tracks as workers attached the engine’s 18 cylinders, one at a time.

Life after World War II: For a while after the plant closed in September 1945, parts of the facility stored surplus goods the military transferred or sold. In 1947, the Internal Revenue Service moved into some of the facility, and would be a tenant for the next 60 years.

In 1949, the building returned to military use when Westinghouse moved in to part of the facility to produce engines, jet engines this time. Westinghouse also leased part of the space to the Bendix Aviation Corporation, with whom they were in a partnership on the engine production. Bendix would become another long-term tenant.

In addition to its work with Westinghouse, Bendix soon had separate contracts with the Atomic Energy Commission for the production of non-nuclear parts in America’s nuclear weapons. That work continued when Bendix merged with Allied Signal in 1983, and until the final closure of the complex in 2014. Demolition on the entire facility began shortly thereafter, and continues now. After what is anticipated to be at least several years of environmental remediation, the federal government has general plans to redevelop the site in conjunction with private developers and city assistance.

LAKE CITY AMMUNITION PLANT – Lake City, Missouri

Location: The Lake City Army Ammunition Plant (LCAAP) sits just south of Highway 24 on 7 Highway in the northeast corner of Jackson County. While the plant is within the city limits of Independence, the plant takes its name “Lake City” from a small unincorporated farm community north of the site. The operation sits on almost 4,000 acres.

Significance to the War Effort: Lake City’s mission has always been to provide the Army with its ammunition for small, military-issued pistols, revolvers, rifles, and machine guns. During its initial WWII operation, Lake City produced nearly 6 billion rounds, still only 13% of total military production. It shared war-time production responsibilities with 12 other similar facilities around the country. Today, Lake City is the army’s only small arms ammunition plant, but its production is dramatically less than it was even twenty years ago, less than 2 billion rounds per year.

Operation:The first facilities at the site had 340 buildings, most related to production, but a large number devoted to services for personnel, especially with regards to worker safety. Not only were there first-aid stations throughout the plant, but there was a separate hospital. WWII employment peaked around 21,000, including a police force, a 640+ member horseback detail used for perimeter security, and a fire department with 82 firefighters.W

The initial operation contractor was Remington Arms, and in its day, the plant was often referred to as “the Remington Arms plant.” As contractors changed over time, it became Lake City, the only constant identity the plant has had. It is also the only defense operation profiled here that still operates to the same purpose as it did when it first opened.

Significance to the War Effort: Prior to WWII, the Army’s only small arms ammunition plant was in Philadelphia, already deemed outdated by the 1930s. In the late 1930s, the Army, anticipating involvement in the war in Europe, devised plans for increasing capacity and modernizing production methods. The Lake City plant was the first of six of these new plants to be built, and served as a prototype for the construction of the others. It was also one of only two of these plants that were put on standby status at the conclusion of WWII.

Life after World War II: When Lake City was put on standby status in 1945, the plant’s production facilities were closed down and stored in place, and for the next five years, the plant was monitored and maintained by the Army’s Ordnance Department. The plant came back on-line in December 1951, with considerable investment on the part of the Army in the facilities and the technology, even though the old production machines remained in place and in use. Remington Arms returned as operating contractor, and would remain so until 1985. Employment didn’t rise to WWII levels, but was still an impressive 15,000. Lake City served the Korean War efforts by producing ammunition with an average annual production of around 1 billion rounds. Also during this time, another 135 buildings were added to the site, and many of the original buildings were modernized. The plant continued operations after the Korean conflict through the 1960s and 1970s, through the Vietnam War, and to keep up, added another 35 buildings.

Remington Arms operated the plant from its opening in 1941 until 1985. Olin Corporation operated the plant from 1985 to 2001. Since that time, a succession of mergers have moved the plant under the operating umbrella next of Alliant Technologies (2001-2015), then Orbital Sciences (2015-2018), then Northrup Grumman (2018-2021). Last year, the modern iteration of Olin Corporation, known now as Olin Winchester, will assume that role. After a one-year transition period, operations will pass to Olin Winchester. Lake City is now the country’s only government-owned, contractor operating facility manufacturing ammunition for small arms.

All of the WWII era original equipment is reported to still be onsite, functional, and for the most part still in use. It sits alongside equipment of every other era in Lake City’s history, up to and including the sophisticated robotics used today.

Next week, we finish up the series looking at three slightly less familiar defense operations, coincidentally all on the Kansas side of the metro – the Sunflower Ordnance Plant in Desoto, the Olathe Naval Air Base, not in Olathe, but in Gardner, and the Darby Corporation, also in the Fairfax district of KCK, and fabricators of some of the most recognizable equipment from World War II.

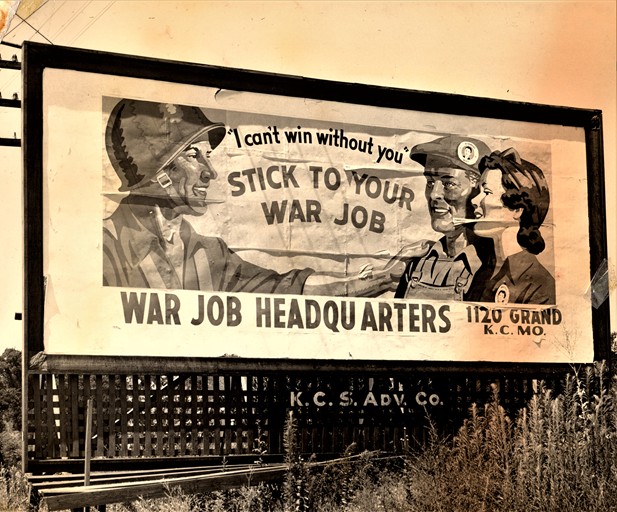

(Featured photo: A billboard encourages Kansas Citians to join the industrial production effort by coming to the War Job Headquarters at 11th and Grand.)