(originally published 12/12/18)

When I first posted this on the original website, it was not coincidentally at a time when the world-wide refugee crisis was at a peak. The crisis is now no less critical, but I offer it in keeping with the current season of holidays around the globe, and Arsenio’s hopeful story.

Included in my book on Waldo is a chapter highlighting the Gillis Home, a provider of support for children and families for more than a century, and the story of Aresnio, an eleven-year-old Spanish boy who in 1942 entered the refugee orphanage system in Europe, then came to the United States, and to Gillis. Arsenio wrote Gillis a letter in the 1990s, reflecting on his experiences there. Arsenio’s story tells of the small kindnesses he enjoyed as a non-English speaking refugee, and what that meant to him at such a vulnerable tine in his life.

Gillis provided Arsenio a chance to prove himself. “An elderly lady was the cook at Gillis and each evening she made out a list of the groceries needed the following day. It was the responsibility of one of the boys to get the groceries from the storeroom. The task was never carried out to the cook’s satisfaction. When the job fell to me she had found her grocery boy. I knew how to operate the scales, was careful not to deliver beets when she asked for beans, put away the cart and made sure the storeroom door was locked. I became the permanent grocery boy and the week’s allowance was increased a dime. At the movies I could buy popcorn with double butter.”

Arsenio benefited from the charity of the Kansas City community. “Sometimes on weekends two Jewish ladies dressed from head to toe in black (driving a black car) would come to Gillis and take (another child) and me for an outing. They would drive us to the sights of the city, visit parks, to the airport where we could watch the airplanes take off and land. We could not communicate with them in English nor could they with us in either French or Castilian. The memory of these ladies in black now brings a smile and a tear.”

Recalling how social workers understandably placed him with a Catholic family in his first unsuccessful attempt at adoption, Arsenio wrote, “What the social workers, the American public and this well intentioned couple did not comprehend was the intensity of our hatred for the Catholic church. It was universally believed by the refugees that the Catholic church complied with and even participated in the cruel reprisals suffered by those who opposed Franco. This abhorrence of the church was reinforced daily. An eleven-year-old could not enter a church that he felt was responsible for so much suffering and even the breakup of his family.”

When Arsenio was finally placed for adoption, he poignantly writes about the end of this chapter of his life. He refers to the social worker who would accompany him to his permanent home when he writes, “How could she know that living in groups of children since 1936 had become the norm for me, and in what was always an energized environment, that I thrived.”

I believe Arsenio’s story is best summed up in his memories of belonging. He recalls how “in the summer heading to the swimming hole (following the trolley tracks!) with our arms on each other’s shoulders knowing we were brothers. Brothers not of common parents, brothers made by common loss, thrown together by chance, drawn together by mutual need. The years spent in the orphanage were the happiest of my childhood in America….It was a time when I reveled in the friendship of young boys, boys like myself who were the victims of others’ failings. Our shared lives … bonded us to each other as brothers and sisters bond. Light skin, dark skin, blond or brunette, all pained by circumstances not understood, all in need of friendship to assuage the hurt.”

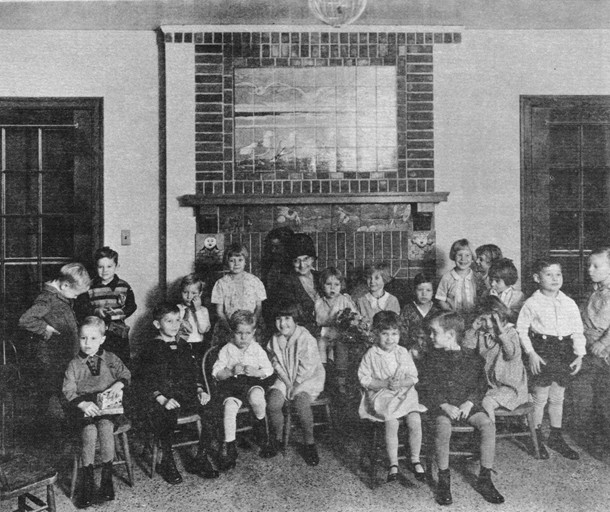

Photo: Mrs. Ella Loose, back row center, with some of the Gillis Home children during her annual Loose Shoe day visit. Circa 1930. Courtesy of the Gillis Home.